|

SPRING is the season that recalls the biblical image of a perfect land so fertile its green hills flow with honey dripping from its hives, like liquid gold in the sunlight. A spacious land covered with pink hawthorn, red cyclamen, and white rockrose. There are the flowers of its myriad wild fruits, and the warm valley air smelling of their nectar.

This curious, supernatural image is evoked every year in the spring by celebrations of the Exodus, which for millennia have alluded to the "land flowing with milk and honey," that divine destination of a people fleeing slavery: the Promised Land. Questions about the particular significance of milk and honey involve literary archaeology, and such pursuit reveals the different layers of meaning these ancient fertility symbols gained as they were adopted and assimilated by different early cultures of the Middle East. What ultimately emerges is a startling image whose core is pantheistic and sexual, as well as both sacred and profane. For us, "milk and honey" originates in the Hebrew Bible in God's description of the country lying between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, namely, Canaan. It is first described as "a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey" and in this way alone when God commissions Moses to lead the Israelites to it. We generally accept the received definition of "milk and honey" as a metaphor meaning all good things God's blessings; and that the Promised Land must have been a land of extraordinary fertility. The phrase "flowing with milk and honey" is understood to be hyperbolically descriptive of the land's richness; hence, its current use to express the abundance of pure means of enjoyment. The original Hebrew (transliterated) is "e-retz za-vat ha-lav ood'vash"; literally, land (e-retz) flowing with (za-vat) milk (ha-lav) and (oo) honey (d'vash). The word translated as "flowing" comes from the verb "zoov" which means to flow or gush. Key to understanding this word in the biblical context is an appreciation of its human sexual associations, given that variants of it are used elsewhere in the Bible to denote the bodily fluids issued from the genitals of either a woman or a man. Thus, in the Hebrew, the word "za-vat" suggests the idea of the land's gushing milk and honey in a sudden and copious flow, as well as its oozing them, and dripping them. A striking feature of honey's legacy in Jewish culture is that, as a testament to the high value put on this particular food, the interpreters of the Jewish dietary laws have apparently made a dispensation for it. These biblical laws reflect the general principle that anything taken from any "unclean" animals such as bees is forbidden. The classic teaching found in the rabbinical literature is that bees do not produce honey, but simply transport the nectar of flowers and store it as honey in their hives. Modern science, however, recognizes that bees actually do produce it, processing nectar in their bodies with enzymes. To argue for honey's acceptance, one early rabbi cites God's own use of it in His praise of Canaan.

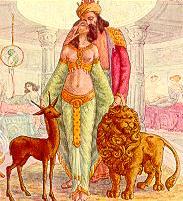

When considering the significance of honey for the Israelites, we must bear in mind that in the Bible there is no implication that it is a cultivated product. Beekeeping was developed by them many centuries later. The biblical bees were certainly wild bees, and various other references made to their honey would indicate that it was considered public property. Wild bees living in the hollow trunks of dead trees and in the protected nooks of rock formations produced honey long before apiculture was invented. In nature, fertile land produces honey by itself and can be seen flowing, quite literally, with it. One clear implication of the presence of abundant wild honey is the existence of ample water and fertile soil that nectar-producing flowers require. An abundance of this wild honey would generally imply other desirable conditions about a land and its climate that people dependent on the earth's fertility for their survival would value. Surely, the ancients observed that honey was most plentiful in areas where their livestock produced the most milk. In these same pastures, rich in greens for grazing, would grow an abundance of flowers for bees. Not surprisingly, milk and honey figure prominently in the oldest cultures and religions of the Middle East. For example, the Egyptians, who kept bees as long as 5,000 years ago, sweetened their foods and wine with it. They also valued honey for its medicinal virtues and for its ability to preserve fruits. They used it as an embalming material, as well as a love potion. The Egyptians, moreover, used milk and honey in their religious rituals. In the funeral ceremony performed for all but the poorest Egyptians, milk, it was chanted, should never be far from the mouths of the dead. Honey was "the lord of offerings and celestial food for it is sweet to the heart: it opens the flesh, knits together the bones, gathers together all the parts of the body, and the dead drink the smell of it." This is why Egyptian royalty were entombed with pots of honey (found unspoiled by modern archaeologists) to help ensure their resurrection in the Other World of their afterlife. In all the earliest cultures in the Middle East, honey was viewed as a gift of divine origin. The ancient Semites attributed its presence to Astarte the goddess of sexuality, fertility, maternity, love and war who was more widely revered among them than any other Babylonian god; and this earth mother had provided them with it long before Jehovah appeared. Milk and honey as symbols of fertility appear in the most ancient writings, and the well-recognized cross-pollination of these early cultures perpetuated them. Each one assimilated them, as in the Bible, where the land's fertility is likened to human fertility and sexuality. Clearly, the biblical image of milk and honey has its roots in the most basic survival needs. It is not merely sensuous, but very sensual, as in the erotic love poetry of the "Song of Solomon," where the fertility figure of milk and honey suggests the paradise of a woman's body. By extension, a land flowing with milk and honey becomes metaphoric of a divine female figure. Astarte's worship by the Israelites was denounced as idolatry, and in the Bible she is referred to derogatorily as Ashtoreth, a form of her name combining the Hebrew word for shame, "bo-sheth." She was associated with profane love. But for a time she rivaled God for their devotion, as with King Solomon of the "Song," who became a follower of her. The "Song of Songs" (as the poem is also known) is replete with allusions to the pre-Hebraic myth of the love of a god and a goddess on which the fertility of nature was thought to depend. It contains some of the most ancient symbols and motifs in the Bible, with their original pantheistic references long forgotten, such as Astarte who was traditionally portrayed as full of sexual allure, like the bride in the "Song."  The enduring legacy of this pantheism is likewise found in the depiction of Canaan's fertility as flowing ("za-vat") with milk and honey, where the original Hebrew with its distinct sexual overtones lost in translation and forgotten implies an earth mother capable of nurturing a people so they can be fruitful and multiply. In this way, the fertility and sexuality of the profane mother goddess, Astarte, form the core symbolism of the biblical image of milk and honey. Jehovah may have assumed her dominion over nature, but the language attributed to Him the language of the early Hebrew people reveals the older worship of her in the sacred eulogy of the Promised Land.

|