Music rots when it gets too far from the dance.

Poetry atrophies when it gets too far from music.

Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading

|

WALDEEN (1913–1993) dreamed of the dance for most of her life, from early childhood to her death. In her last years, even though she was suffering from an increasingly debilitating heart condition (for which she preferred herbal remedies), she still was very much the vibrant woman she had been in her youth. The dance, like poetry, was always in her blood — the daring blood of the "Texas girl," as she was called when she made her New York debut, who at fifteen left classical ballet in order to find her own voice, to speak freely with her body, hands and face. The blood of the young dancer who, at twenty-five, having already distinguished herself here and abroad, made Mexico City her home, inspired by the vitality of the arts in Mexico where she believed art and life were fused into one reality — and where the people loved her. She created dance for more than half a century. Her remarkable career as a prima ballerina and choreographer becomes all the more remarkable when viewed together with her work as a translator of verses from Canto General (General Song, 1950), the Latin American epic written by her friend and admirer, Pablo Neruda, the Chilean maestro destined for the Nobel Prize. Indeed, her verse translations from the Canto published in the early 1950s introduced many to the "expansiveness," as Allen Ginsberg put it, of Neruda's voice. The republication of these poetic translations in 1989 brought her literary work to our attention once more. But Waldeen, the Pan-American pioneer of modern dance, has yet to receive the recognition she deserves in the United States for her important contributions to both dance and poetry. As the founder of a modern — truly Mexican — form of ballet, and as one of the earliest voices of Neruda in English, she boldly expanded the bounds of our own speech and sensibility in these two different but sister arts.

Born in Dallas, Texas, Waldeen was the daughter of parents whose faith and support from the start nurtured her career as a dancer. Her beautifully mysterious name — inspired by Thoreau's Walden — was given to her by them: it is neither a stage name nor a nom de guerre, but her Christian name. More important, her parents created a most unusual home. Her father had come from Prussia as a child, brought here by parents who rejected Bismarck's social policies. He grew up to become an active Transcendentalist and rebellious liberal. Trained as an artist (engraver), he made his living in the printing business. Her mother, a genteel woman from Georgia, was a proper Southern lady with a great respect for the arts. She herself was a pianist who sacrificed her career for family. Together they bestowed upon their daughter a rare mix of personal traits that would shape her destiny. Waldeen never had any other dream, she said, than to be a ballet dancer. At the age of four, she started taking ballet lessons. Her family moved to Los Angeles when she was seven, and the next year she started her formal ballet training there with Theodore Kosloff, the Russian dancer-cum-movie star, who would guide her technical development at his famous School of Imperial Russian Ballet. She began to write poetry around the time she arrived in California — lyrics in which the young girl expressed her budding passion for life. She lived comfortably with her parents, brother, and sister in a newly built house in West Hollywood, on Orlando Avenue. It was a middle- to upper-income area at that time. Nearby were the small estates on Kings Road, where Theodore Dreiser lived, and where the architect, Rudolf Schindler, built his famous studio-residence in 1922, considered the first modern house to respond to the unique climate of California. Her father's printing company, Castle Engraving, was considered the best of its kind in town, and the family lived well. With neighbors in the movie industry, there was a good measure of theatre and show business in her personal world, amid the local stars of Hollywood. All the while the dance world became central to her identity. Waldeen's promise as a dancer was recognized immediately by Kosloff, who soon invited her to dance with his ballet company. At thirteen, she danced as a soloist for the first time, performing for the Los Angeles Opera Company. Two years later, breaking with Kosloff and conventional Russian ballet, she began to fuse both modern and classical dance forms. In 1932, she toured Japan with Michio Ito's group, dancing her own compositions. Returning to California, she divided her time between teaching and concerts. (It was around this time that she stopped using her family name, von Falkenstein.) She gave a series of solo concerts up the West Coast and into Canada, and in 1934 went to Mexico on a tour with Ito during which she gave fifteen concerts in Mexico City. Her experience there aroused a fascination with Mexican life and art. Consequently, on her return to Los Angeles, she began to study Spanish so that she could best pursue her new-found passion. While in California between 1934 and 1937, Waldeen danced in numerous Hollywood films, working with such stars as the Marx brothers, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It was the golden era of the Hollywood musical. She danced in chorus lines — toe, tap or barefoot, whatever dance work she could find — to raise the money necessary for coming to New York to present her own dance compositions. She also helped to organize her fellow dancers into the Screen Actors Guild (after an episode on a sun-baked set where dancers were compelled to work for more than two grueling hours on pointe), and through this union work she further developed a commitment to social justice that would later flower in her own ballet.

In 1937, she went to New York to teach dance and to see what was happening on the dance scene there. What she found was an established "School of Modern Dance" headed by Martha Graham. While Waldeen prepared a program of her own compositions for what would be her New York debut, she taught modern dance, dance history, and choreography at the Neighborhood Playhouse and the Nicholas Roerich Museum. This debut finally took place at the Guild Theatre in February of 1938. The critics noted that her training in ballet technique was apparent in much of her work, but that the influence of the early pioneers of modern dance, in particular Isadora Duncan, was even more prominent. Waldeen's style was essentially lyric like that of Duncan, whose book — a gift given to the young ballerina from her mother, a decade ago in Chicago, where she last danced classical ballet with Kosloff — had opened her to new possibilities, such as holding her hands the way she had seen hands in El Greco (Kosloff blew his top when she told him in a rehearsal that she wanted to hold her hands differently). Waldeen's fluid sense of movement also reflected her training with Ito, in the sharpness of her attack.  The program — all her own creations — included the music of Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Charles Jones, Edward Morris, a specially composed group of "Fragments from Old Spain" by Verna Arvey, and a special arrangement of Afro-American spirituals by Harold Forsythe. In her "Dance for Regeneration," based on Wallace Stevens' poem "Sad Strains of a Gay Waltz," she projected a waltz-allegory that captivated her audience. The more receptive critics appreciated what was most individual about her dance work, aside from the artistry of her composition, namely, her concept of movement and her translation of it into rhythmic fluidity within a perfectly controlled technique. But the critical response of New York's dance establishment was decidedly cool. Typical of this response was the comment made by Jerome Bohm, whose review of her debut appeared in the Herald-Tribune: "Only here and there, as in the 'Dance for Regeneration,' … was there a suggestion in an occasional gesture or movement of a more modern [than Duncan's] approach, although at no time could her efforts be closely associated with the newer trends in her art." Waldeen was at odds with the prevailing dance politics in New York, for she did not offer the cold angular dance of the fashionable Graham. Waldeen was a much more melodic dancer. Although her work displayed an austerity of movement, it was distinguished by a simplicity of lyric clarity not in step with the Graham school. As a result, she quickly became discouraged and realized she had to look elsewhere to find an audience that would embrace her dance. The success of Waldeen's earlier tour of Mexico led to the break she needed, to the most dramatic move in her life and career. In early 1939, she left New York for Mexico City, at the request of the Mexican Ministry of Education, which had invited her to return to create a national ballet and school of modern dance under the auspices of the Fine Arts Department (Departamento de Bellas Artes). It was a good time for her to go to Mexico. The arts were flowering: the muralist movement was at its peak, and in music and literature Mexico was coming into its own as well. She was swept away by the excitement of this period, as she recalled:

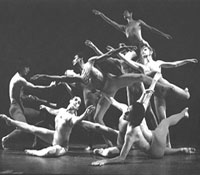

She organized the Ballet de Bellas Artes which gave its first performance in the fall of 1940. The dance program explained that its purpose was to crystallize the life and aspirations of Mexico through dance. Waldeen's dream was "to create a new and healthy dance, with real meaning for the Mexican people; a national dance in spirit and form, but universal in its scope." The Ministry of Education, which subsidized Waldeen, was encouraging the creation and development of a Mexican choreographic movement "free from both false folklorism and the imported ideas and forms … that cannot take root in Mexico."  In creating the Ballet's repertoire, Waldeen and her dancers carefully drew on the rich heritage of the traditional arts of Mexico. She was, moreover, committed to using "the universal technique of the dance, from both the past and the present." The Ballet would rely not only on Mexican artists "aware of Mexican life," but also on foreign artists "possessing technique unknown in Mexico," and included classical and contemporary foreign works in its repertoire because they served "as artistic stimulation for the new generation of Mexican dancers." The Ballet de Bellas Artes was met with thunderous applause and armfuls of flowers. The newspapers in Mexico raved about it. Excélsior said, "Waldeen's genius has transformed the phenomenon of our life, Mexican life, into an aesthetic phenomenon." El Nacional celebrated "the best ballet company seen in many years … destined to pass into the history of our national art as one of the most notable developments of the age." The now-famous ballet La Coronela (The Lady Colonel), performed as part of the first program in 1940, was choreographed by Waldeen as an elaborate spectacle; Silvestre Revueltas, Mexico's leading composer, had written the music during the months before his death (listen). This satiric ballet, which focused on Mexico's Revolution of 1910, was based on the popular engravings of the genius José Guadalupe Posada, and it marked the beginning of a truly Mexican form of ballet.

Waldeen met Neruda soon after he arrived in Mexico, in 1940, as Chile's consul general. She remembers: "He was a big bear of a man, absolutely charming. He had a wonderful sense of humor. He was a tremendous conversationalist, much like Diego [Rivera]." They were part of the same circle of friends and artists, such as Revueltas, with whom she was collaborating. He had studied the violin and composition in Mexico City, in Austin, Texas, and in Chicago and had conducted an orchestra in Mobile, Alabama, before becoming assistant conductor (1929–35) of the Mexico Symphony Orchestra. In the compositions he wrote when back home in Mexico City, he suggested folk derivations without quoting actual Mexican folk songs, often achieving a powerful rhythmic drive that would end fortissimo after a hammering crescendo. His major works were symphonic poems on Mexican subjects, like the music of La Coronela. When the composer died in the fall of that year, just before the debut of the Ballet de Bellas Artes, Neruda wrote an elegy for him which forms part of his Canto, and it includes these tender lines to Revueltas:

In fact, Neruda was writing essential parts of his epic when he was living in Mexico, in particular the celebrated section, "América, No Invoco Tu Nombre en Vano" (America, I Don't Call Your Name in Vain). During this period, Waldeen formed a lasting friendship with Neruda, who stayed in Mexico as the Chilean consul until the fall of 1943.  Neruda admired not only Waldeen's ballet, but her poetry as well. Before he left Mexico he proposed to her that they do a bilingual book together in which he would present his translations of her poems, and she her translations of his. But the young dancer passed up the opportunity (she was "young and foolish," she said in retrospect). Her poems can be found only in magazines now; she has yet to publish a collection. The ones that she showed Neruda were terse and formal with an air of mystery about them, as her "I Shall Not Care," published when she was eighteen:

And her "Riddle" composed around the time she was showing her verses to Neruda:

Although her poetry does not embody the political vision of Neruda's work, it clearly shares a lyric intensity. "The Quartz Heart," another poem written during the same period as her "Riddle," reveals her poetic voice that came not merely from the throat, but from deep within her:

Her language reminds one of Emily Dickinson, and like Dickinson, Waldeen voiced an independent spirit. She too had no desire to be strictly confined to rhyme or reason.

For Waldeen, technique was always an instrument, not an end in itself. Thus, "Mexican technique" did not mean copying folkloric or prehispanic styles. Rather, it meant creating movement with those elements of Mexican culture in mind. One of the early pieces she created in Mexico, "En la Boda" (At the Wedding), was based on traditional sones from the state of Jalisco in the west-central part of the country. "But there was not a single authentic folkloric step in it," she said:

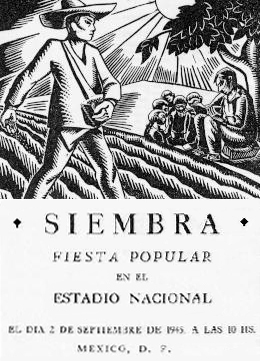

She believed that to create movement for choreography in Mexico with a Mexican theme, one must forget technique, and create movement for that theme. Waldeen flourished with the Ballet de Bellas Artes for two years. When the education minister was replaced she suddenly found herself out on the streets with no studio and no income, but, through the support of her friends and students, she continued to dance. The Ministry of Education soon went through another reorganization that welcomed her back, and she was given a subsidy that enabled her to form a new dance company known as the Ballet de Waldeen which enjoyed great success. Her genius found expression in other ways too. She was the choreographer of the celebrated Mozart Festival held in 1944 in Mexico City under the direction of Sir Thomas Beecham. During the next two years, she staged the dance sequences for seven Mexican films, among them Bugambilia and Las Abandonadas, starring Dolores del Rio and directed by Emilio Fernandez.  In 1945, she choreographed the first of what she has called her "mass ballets," multi-media events in which literally thousands would take part. Performed as part of the Ministry of Education's new literacy campaign, Siembra (Planting Time; based on the native dance of the seed-sowers of Michoacan, a state in central Mexico, on the Pacific coast) was the largest mass ballet she ever created, with 5,000 participants, including the orchestra, the chorus and 2,000 dancers. Like her future mass ballets, Siembra was neither a gymnastic nor geometric production, but a brilliantly conceived expression of the dance which appealed to the so-called masses or common people as well as to the more refined connoisseurs of the art. Waldeen's dance classes were thriving again. She was well established as a prima ballerina and choreographer in Mexico when, in 1946, she felt a need to try New York once more, and so she went there to work, performing with her own group of American dancers in recital halls at such places as Hunter College, Brooklyn College of Music and the YMHA (for the Choreographers' Workshop), and teaching dance and choreography at Hunter and the New School. It was in New York that she started translating the poetry that would form part of Neruda's Canto. Her friend Luis Enrique Délano, a Chilean writer and diplomat who had served in Mexico with Neruda as vice consul, asked her to translate some of it, including his "Let the Rail Splitter Awake," originally composed in May 1948. Her creative energy was boundless: after long days of teaching dance and doing choreography she went home close to midnight to work on her Neruda. Her translation of his homage to Lincoln would make its debut appearance that year in the October issue of Masses & Mainstream, with a special fanfare by the editors of this new monthly magazine of the Communist Party. She was also making translations of his other new poems. Expanding her work as translator, in addition to English, she translated two of his earlier poems into a dance that she performed with four other dancers, in April, for a Choreographers' Workshop program at the Hunter College Playhouse. She called the two-part dance Residence on Earth, after Neruda's book that preceded his Canto. The first part was titled "Hymn and Return" and subtitled "Song to Chile," after the 1939 poem to be included in the Canto, and the second part "Spain in the Heart," after the section in the third and final book of the Residence, with her translation of the poem in it titled "Song for the Mothers of Dead Loyalists." A vocalist and voices were also part of the work, together with original music featuring flute and violin. But her experience in New York was less than ideal. She was still very much at odds with the dance establishment; all the while, her dancers in Mexico were writing to ask her to return. And so, in August 1948, she went back to Mexico, re-forming her school and choreographing for a new group, Ballet Nacional, with which she would travel into remote regions of the country, dancing in rural schools, village plazas, stadiums and fields. In September 1949, Waldeen performed a dance adaptation of "Let the Rail Splitter Awake" at the closing session of the six-day-long American Continental Congress for World Peace, held in Mexico City. Her elaborate ballet featured a dozen dancers wearing costumes and masks, accompanied by a recorded dramatic reading of her translation. This reading had been arranged for three voices by Asa Zatz — her colleague (lighting designer; veteran of Stage for Action) and husband (1948–54; they stayed friends for life). The three readers were the Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas, the Bolivian painter Roberto Berdecio, and Neruda himself. The recording of the translation was inter-cut with original music written for her ballet by Hershy Kay — the now well-known New York orchestrator — based on North American folk songs documented in Alan Lomax's work, and featuring a guitar, cello, trombone, clarinet, and percussions. During the conference Neruda was staying at Waldeen's home. Also there along with Zatz was guest Lloyd Brown, an editor at the leftist monthly magazine Masses & Mainstream. Brown recalled the poet telling him (in English) about the "Rail Splitter," the first major poem he wrote while in hiding as a fugitive (1948–52): "I felt that I wanted to talk to your people." Waldeen's translations of selected sequences from the Canto General were published the following year in a chapbook titled Let the Rail Splitter Awake and Other Poems [full text]; the original Spanish of the whole poem appeared in print the same year — the fruit of twelve years' labor by Neruda. When he first read her translations in manuscript, he was deeply moved and wrote to her: "Thank you, Waldeen, for your poems of my poems, which are better than mine."  The widely distributed chapbook, which went through two subsequent printings in the early 1950s, featured an essay by the poet and "poems" from the Canto, most of them translated by Waldeen. Its republication in 1989 by International Publishers attests to the lasting power of both the poetry and translation. New York-based Masses & Mainstream, the original publisher of the chapbook, was a well-known source of Marxist literature at the time of the first publication, and Neruda was no stranger to its audience. Composed when the poet was in exile from Chile — he was forced to escape as an outlaw in February 1948, crossing the Andes on horseback by night with the manuscript of Canto General in his saddlebag — "Let the Rail Splitter Awake" (the translation was revised a bit for this publication) invokes the figure of Lincoln as a freedom-loving hero of the Americas. It is in many ways an appeal for world peace, as well as a petition to the United States for Pan-American harmony during the early years of the Cold War. Neruda celebrates the common people of North America who, like the common people of South America, must struggle against the hateful policies of multi-national corporations. The chant of the penultimate fifth section builds to a vision of modern America revitalized by Lincoln's democratic spirit:

Through the force of its verbal dance and music, the translation made by Waldeen successfully brings into American English the colloquial image-driven language of Neruda's verse. Her rendering of the two final sections of "Let the Rail Splitter Awake" was adapted by Allen Ginsberg some thirty years later, and included in his collection titled Plutonian Ode and Other Poems (1982). Ginsberg, who had first read Waldeen's translation when, in the early 1950s, he was a young poet enamored of the bardic voice, was clearly moved by her Neruda. His subsequent adaptation is a fitting tribute to Waldeen, as well as an expression of gratitude. Waldeen offered only a glimpse of the range of Neruda's immense Canto in the 1950 Masses & Mainstream publication, Let the Rail Splitter Awake and Other Poems. In addition to "Let the Rail Splitter Awake," her translation of Neruda's masterpiece, "The Heights of Macchu Picchu," introduced his poetry at its best. This sequence would later receive much critical acclaim. Her translation was among the first in English; the sequence has been published in several later renderings by Nathaniel Tarn (1967), John Felstiner (1980), David Young (1987), Jack Schmitt (1991), Stephen Kessler (2001), and Tomás Q. Morín (2014), among others. Waldeen's re-creation of the dance of Neruda's poetic language, together with a fidelity to the literal meaning of his words, distinguishes her translation, as illustrated by the opening lines (listen to Neruda reciting them in Spanish):

The close of the Macchu Picchu sequence which forms a statement of Neruda's commitment to creating a voice for Latin America's peoples, past and present, reflects Waldeen's commitment to the same artistic mission:

Her translations of other sections of the Canto appeared in the now-defunct California Quarterly in 1952 and 1954, edited by friend Sanora Babb. (They remained the only published English rendering of major parts of the poem until 1991, when a translation of the entire work — long overdue — was published.) Among them was the Canto's opening, "America My Love (1400)":

These verses and others rendered by Waldeen have been obscured by time. Most of her Neruda is not available now for another reason, for she actually translated a third of the 568-page Canto and published only a fraction of what she had composed. (Neruda had given her his formal permission to translate the entire Canto.) The political climate here during the years of the Cold War made publication of this work difficult, to say the least. Neruda, after all, had joined the Communist Party in 1945. The poetry that followed his experience in the Spanish Civil War, written after the famous love poems of his youth and the masterpieces of his surrealist verse from the early 1930s, was often distinguished by its partisan stamp. He charged the Canto General with his politics. "Let the Rail Splitter Awake," for instance, surely alienated many people here with its romantic passages in praise of Stalin and the Soviet Union. Not only was the poem itself considered offensive, it earned Neruda the 1950 International Peace Prize — shared with Paul Robeson and Picasso — awarded in Warsaw, and his acceptance further kept the poet at odds with both the literary establishment and the government of the United States.  By 1952, with the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act (the immigration law that provided for rigorous screening of aliens to prevent so-called security risks and subversives, especially Communists and their fellow travelers, from entering the country). Waldeen herself was on the way to becoming persona non grata here. But she had found a loving homeland in the "other America" where she could freely pursue her art. During the years that followed, she would perform in the major cities throughout Central America, often going as well into the provinces to perform for peasants. Her first marriage of six years ended in 1954, the same year she gave her last public performance as a dancer. She soon remarried and became the mother of a son; this marriage, to a Mexican, brought her Mexican citizenship. In 1962, she went to live in Cuba, at the request of the government, to create a national ballet in the revolutionary tradition of her Mexican ballet, an activity which further heightened the U.S. government's desire to keep her out of the country. Returning to Mexico four years later, she would create dances and teach and lecture. In 1975, she directed her fifth and final mass ballet, The Edge of Dawn, with 500 participants. It was her last major public performance, as her health (heart) was beginning to fail, and physically she could no longer meet the demands of her creative work on the stage.

In her last decade, she wrote poetry as well — in English. She gathered this work in a manuscript titled "Death Is But Another Dancer (Poems for Aging Women)," to be her first book of poetry. It includes two hopeful epigraphs, one by Neruda and the other by Blake. Building up to a vision of acceptance of her own death which she sensed was approaching, the title poem opens with her reality:

Despite the debilitating angina she suffered in her final years, she was also trying to interest publishers in another book of prose which would focus on the earth/mother goddesses of ancient Mexico and Greece, as revealed through myths, dance and poetry. Crowning her career in dance, in 1988, Mexico's National Institute of Fine Arts gave her its first annual José Limón National Dance Award, regarded today as the country's most important dance award. The following year, she directed a film version of her ballet Tres rostros de Carmen Serdán (Three Faces of Carmen Serdán) for Mexican television based on the life of the revolutionary heroine. She called it a "choreographic poem." Its premiere performance in the mid-1980s in Mexico City was received enthusiastically by the audience, with many members in tears. Looking back on its reception then, she said: "I find it fascinating that both my first (La Coronela) and my last dances were the ones to elicit the most excitement from my public." As a dance theorist, Waldeen early on rejected the notion of pure dance, which assumes that the artist is a world unto him/herself, a world free of the disturbances of society. She argued that "dance is inseparable from reality." Her dance theory, based on her understanding of "the dynamics of the historical growth of all art forms," led her to envision "the irrevocable interrelation of the dance with other arts" and to claim that "dancers are not isolated inferior inhabitants of the great world of art." Early in her career, she also understood that the fashionable "despair-movements" in modern painting, literature and music had their equivalents in dance, as her observations made in the late 1940s demonstrate:

Waldeen herself achieved what she demanded of dancers: an honest success, the slowly constructed, soundly complex, aesthetically fresh art form, capable of arousing enthusiasm in universal audiences through its inspiration, beauty and humanity. In Neruda's words, her contribution to dance is "a shining example of how, without being cut off from the world's realities, art can bear its essential flower."

Waldeen's passion for his Canto General flowered in the dance of her mother tongue. The recognition she deserves for this influential contribution to our poetry is late in coming. Her other writings merit attention here as well. What is long overdue, and embarrassingly so, is our recognition of her landmark accomplishments as the Pan-American pioneer of modern dance. |